The TE(P)P is an actual Party formally registered with

and has the Party Reference

RRP 4755321

The Party’s Leader, Nominating Officer and Treasurer is

Michael George Gibson

The Party’s Other Specified Office Holder is

Ms. Dorli Nauta

who is designated

The Party’s Helpmate

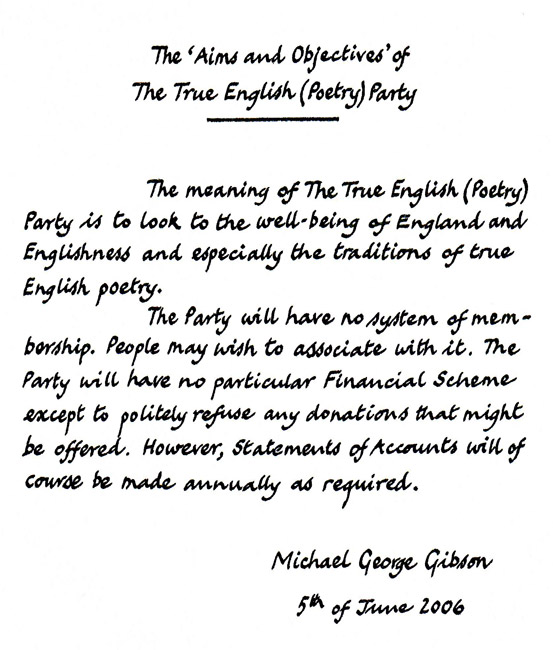

The Party was established with the following statement of its constitution:

The Party’s Manifesto – 2010:

The True English (Poetry) Party

A MANIFESTO 2010

i. The True English (Poetry) Party has no politics or policies in the full sense. The Party bases itself as it were in an England seen to be the home of an English nation. The language which originated in the south of an island that also comprises the countries of Wales and Scotland is now of course widely spoken throughout the world.

The Party is particularly concerned for the well-being of English poetry ~ and, indeed, of the English language ~ and of the land of England. The Party sees proper husbandry of the land (and, of course, of the sea and air) as a duty. We have a duty in common sense to cherish our soil and water resources and to grow as much as we can of our own food in a ‘sustainable’ way.

Regarding poetry, which is the Party’s field of particular expertise, we consider that we have a like duty to conserve and develop what is in some ways an important national and indeed international resource. Poetry is rightly regarded as a valuable cultural component. It is good that we teach our children something about the best English poetry that has been made over the last 1,300 years and of the practices and techniques that produced it. We should also help children to see that poetry was and is a rhythmic form of writing or speaking that is different from other sorts of ‘word things’. Thus we need to be able to say clearly what poetry truly is.

***

ii. Unfortunately, there is much muddle and confusion in this matter, and this is to be deplored. The ‘world’ of poetry is a curious one. Wonderful things may be found there; but there is also much silliness in the field of English ‘verse’.

Consider these states of affairs:-

- Someone may be a Professor of Poetry in a British university yet be unable to give a simple and reasonable account of what poetry truly

- Someone may be awarded an O.B.E. for ‘services to poetry’ yet not be able to give a clear and reasonable account of what poetry actually

- A Professor of Poetry in an English university may declare that English poetry does not begin until the time of Shakespeare.

- A ‘Chairperson’ of an organisation in England calling itself The Poetry Society cannot give a simple and reasonable definition of what ‘poetry’ and a ‘poem’ truly This organisation, which is in part publically funded, has close links with the country’s educational authorities.

- Someone may be made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature for work in the field of poetry who cannot give a simple and straightforward account of what poetry truly In an important book on poetry matters this Fellow shows considerable ignorance of English poetry and a basic ineptitude in the formal analysis of it. This person was a ‘Chairperson’ of the Poetry Society.

- Teachers in Primary Schools in this country are required to teach ‘poetry’ as part of the National Curriculum. These teachers are unlikely to be able to give any clear and simple account of what English poetry actually They are sensibly encouraged to introduce the ‘Limerick’ form as a type of poetry. Yet a Professor of Poetry in a British university who has received an O.B.E. for ‘services to poetry’ has declared on the BBC ‘Today’ programme that the ‘limerick’ is not poetry at all.

Clearly, then, the ‘world’ of poetry is in some respects a somewhat silly and muddled one.

***

iii. But does any of this matter to the world at large?

It does.

Clear thinking is needed in all fields of human activity, and all fields of human activity are interrelated and connected.

Insufficiently clear thinking would seem to be evident in many matters of global political concern. Muddled thought, and deception and self-deception, may endanger the well-being of us all.

For instance, in the matter of ‘the 2nd Gulf War’ and the invasion of Iraq, muddle and nonsense have prevailed. Our Foreign Secretary of the day tells us that a) he thought that the plans for invasion were illegitimate, but b) he nevertheless voted to commit this country to war.

In the matter of global climatic conditions, and resources for life; it is clear that there are dangerous changes occurring to which human industrial and technological development probably contribute, and that there will be increasing scarcity of resources. Yet there is no clear national or international statement of the fact that ‘there are too many human beings wanting too many of the “wrong” things’, and no clear resolve to address the problem. The simple sense that each of us should try to use less of the world’s finite resources (and perhaps enjoy the process) has not yet taken real hold and is not firmly enough encouraged.

The True English (Poetry) Party seeks to promote good sense and clarity with regard to the matter of poetry in particular, as a contribution to good sense in all matters generally.

***

iv. By way of conclusion, here are some further thoughts:-

Bang or Whimper?

As a road-side bomb thumps near Baghdad,

Swipes the legs from some poor home-grown lad,

Though we don’t know who lied,

Rest assured that he died

In the arms of some ‘Westminster Dad’.

***

Will the day that our leaders agree

That this finite blue globe isn’t free

Come when, trouser-legs rolled,

They are finally told

There’s no ice for the next G and T

***

Yes, it’s easy to rhyme out our bile

While each feathers his nest with fixed smile;

But it’s not ‘Them’ and ‘Us’,

We’re all on the same bus ~

Let’s get off, walk and talk the next mile.

Michael George Gibson

Spring 2010

The assertions made in part II of this Manifesto are widened and supported in papers presented on this website.

A preliminary attempt to give an answer to the question ‘What is poetry?’ is appended.

Its most important foundation document is this paper.

ON ENGLISH POETRY AND POEMS

Michael George Gibson

There is some perplexity in people’s minds as to what English poetry and a poem may be. Poetry was, and to some extent, still is, an important part of our culture and sense of nationhood. I therefore propose to make a definition of English ‘poetry’ and a ‘poem’. In fact these terms were not widely used in English until the 16th century: but I think that it is fair to apply them to some things which were made in this land in earlier centuries.

We have some written stuff from the 8th century onwards which may be called English poetry. In Anglo-Saxon times there were word-things then called ‘lays’ or ‘songs’ which were of essentially the same nature as the things later called ‘poems’. Anglo-Saxon lays and songs were made according to ‘lay-craft’, ‘song-craft’ or ‘word-craft’. The Anglo-Saxons spoke of their lay-craft or song-craft as one in which the parts of the lay or song were ‘verses’. The word ‘verse’ meant a ploughed furrow both in the sense of its line and length and in its turn to make another furrow. These early makers also spoke of theirs verses having ‘feet’ and of their being ‘metered’. Their verses were by and large of much the same length and had much the same amount of stuff in them as the others in a particular ‘fitt’.

The word ‘rhythm’ was not used in those days but was implicit in the word ‘song’. Their songs were markedly rhythmical – as is the case, one presumes, in all early cultures. This was so that anyone could partake in the song and often the dance that might go with it. This is why the word ‘foot’ was used in describing and defining the craft.

The metered verses of the Anglo-Saxon or Old English poetry were further shaped by means of a system of internal correspondences of consonants or vowels at the beginnings of some of the words in each verse. This we now call ‘alliteration’. It is clear that in most Old English poetry a verse usually had in it four main beats or pulses which were linked by the initial sounds of the words rather than their endings – though this was not usually the case for all four beats in a verse.

In due course ‘end rhyme’ came to be used at the ends of some verses, and this system of shaping poetry eventually overtook the alliterative way during the Middle English period. But the metering out of verse into feet was always done. It is to word-things made up of metered and rhymed verses to which the words ‘poetry’ and ‘poem’ were later applied. There were of course other aspects of the use of language that came into the consideration of the nature of poetry: but these were not fundamental to a definition of ‘poetry’ or a ‘poem’.

It was several centuries before any very different way of doing things was tried. Towards the end of the 19th century ‘free-verse’ – from the French vers-libre – became a technique of writing. But I hold that the term is illogical, a nonsense.

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms (1990) defines ‘free verse’ as:

a kind of poetry that does not conform to any regular meter: the length of its lines are irregular, as is its use of rhyme – if any.

The definition is exact and right except in one respect: it contained a wrong use of the word ‘poetry’, which should be replaced by the term ‘writing’ or ‘word-stuff’, or some such.

In its original sense a verse, or furrow, was metered out and turned in accordance with a system of related furrows (which of course all accorded with the form of the field). This accordance was and is essential to the craft of ploughing and the craft of poetry. ‘Free verse’ is a contradiction in terms: a verse is by definition metered and therefore not free – it cannot be both.

There is something of the same sort of confusion in the matter of rhyme. ‘Rhyme’ means identify of end sound in words.’ Anything less – be it called ‘half-rhyme’ or ‘part-rhyme’ or whatever – is not rhyme, it is other than rhyme.

In the last hundred years writing styles have changed more quickly. Very different things are presented to us as ‘poems’. Trying to find new ways of doing things and new things to make are natural human traits. It is also natural to look for the differences in things and to find words with which to describe and name them in order to discriminate between one thing and another.

‘Songcraft’, later called ‘poetry’, was and is the making of word-things according to certain clear, objective, defining and essential rules and techniques of metre and alliteration and rhyme. These things may be called ‘poems’. To avoid confusion, word-things not made according to these rules but according to some different – and, one hopes, objectifiable – rules, should, as things of a different kind, be given a different name.

References:-

The Oxford English Dictionary

A Thesaurus of Old English (King’s College, London. 1995)

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms 1996

The story of the Party’s development up to the time of its formal registration may be found in its archive:

[Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3] [Part 4] [Part 5] [Part 6]

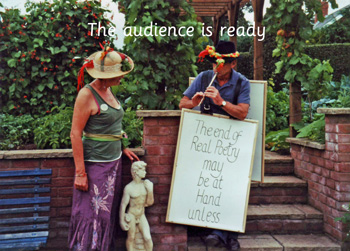

A trial launch of the nascent

True English (Poetry) Party at The Ledbury Poetry Festival 2006

Michael and his agent and helpmate, Dorli Nauta

at the comfortable Orchard Cottage base.

But had the machine perhaps been commandeered by our opponents?

…by Ms. Ruth Padel, Chair of The Poetry Society, with Ms. Jo Bell acting as a diversionary buffer…*

Mr. Tony Walton and Mr. Roy Lee Sadler later dispute the definition of ‘true poetry’ offered by Mr. Gibson.

*In an article the next month in The Guardian, Ms. Padel falsely claimed that she had been heckled. This matter has now been taken up here.

I wrote to Gordon Brown on the 8th October 2006: